(This letter was originally written in Oct-Nov but never distributed)

Of Foreign Lands and Peoples

If you are on this email list or know about this newsletter you already know I lived in Bangladesh as a child. It has been my fun fact when introducing myself here for the last 7 months. Whether meeting Salvationists from across the country and asking apni janen Greg Warkentin? Shey amar baba. (Do you know Greg Warkentin? He is my father). Or meeting other expats who ask how long we’ve been in Bangladesh to which Jess usually replies, “7 months, but Jahred lived here as a child.”

While true, I feel this history has complicated my relationship to the country. The next few questions people usually ask after finding out I lived here are: do you speak Bangla? and what changes do you notice? My answers are underwhelming; I don’t speak Bangla (at least I didn’t upon arrival) and I don’t notice any changes because I was too young to really remember things like that, and lived in very particular isolated circles.

During our time at MTI I came to realize that I wanted to live in Bangladesh differently than my family had in the late aughts. Like many grade school children, my family’s life in Bangladesh was centered around my sister and I’s schooling and church. We attended an English-speaking international school and a church with people from across the globe. Together with our peers we were foreign people in a foreign land. Our primary focus was never trying to embrace Bangladeshi norms, customs, or culture. Rather than trying to adapt to Bangladesh customs we rooted ourselves in our foreignness, spending time at international clubs with foreign friends, eating foreign food. We moved to a foreign land to remain foreign. Jess and I wanted to do things a bit differently.

Dreaming

It was a nice thought: Move to Bangladesh, do as the Bangladeshis do, live as Bangladeshis live, speak as Bangladeshis speak, eat as Bangladeshis eat, etc. But the reality is we are and always will be foreign in Bangladesh, no matter how much Bangla I learn or how much kichuri I eat. Some weeks I feel like I am living a new and completely Bangladeshi life. Particularly when I am out of the city in Jashore, eating spicy curry and rice everyday, getting cha (tea) from the local chawala stand and suffering through a cold shower because there is no hot water. Yet, most other weeks I feel shame at home because we frequently shop at the supermarket instead of the fruit stalls, go to a coffee shop instead of the chawala, and I find myself writing this letter sitting in the international club of which we are members.

On a video call with friends who recently moved to South America, they asked what local customs we’ve adopted. They shared that they’ve enjoyed drinking a local herbal drink each morning through a filtered straw. Oddly, I did not have any particular habit to point to. Jessica has adapted to wearing Bangladeshi shalwar kameez outfits on most days, not simply out of necessity but because of the comfort and style. Several people have said that when she wears Bangladeshi clothing she could pass as someone from the indigenous Garo community. And of course shey dudh cha pochondo kore (she likes milk tea), which we are served every morning at the office. But several habits I hoped to adopt, I have opted for a more comfortable alternative. I wanted to make a habit of playing carrom board with our guards and gentlemen who hang out in our garage, or buying produce from a market outside the neighbourhood because it is cheaper and fresher than the produce in the supermarket. I want to take Hindustani music lessons and I very well might still begin these things. But still our default evening is to stay in our A/C apartment and shop at the supermarket where the shelves are lined with a variety of international import items.

You may think I am being rather pessimistic, and I recognize that I can often look back too far with a judgmental eye. The missionary stories we hear the most are usually the ones of people ‘roughing it’ in the bush or taking on extreme lifestyles to reach the most vulnerable. When we feel a call to do ministry in a foreign land it can be easy to look at these stories with a sense of desired exotic idealism. That there is a particular lifestyle and look to the traditional picture of a ‘missionary.’ And when I hold the memory of my own family’s experience to this picture it can be hard to find surface level comparisons. It is easy to dream and say that when I am here I am going to do it the ‘right way’, but that thinking actually doesn’t ground me or keep me close to the reality God has put in front of us.

As time goes on our dreams, desires, and expectations for what life, work, and ministry will continue to look like here constantly shift and change. We acknowledge the reality that most Bangladeshis live in an extremely urban environment and with that comes many western accommodations/ comfortabilities – by engaging in some of these things we are having no less of a Bangladeshi experience than if we were to avoid them.

Child Falling Asleep

Another great lesson from MTI was that of healthy goodbyes: Saying goodbye to all things in your old life and mourning them to make space for new hellos in your life in a new place. This applies to more than just people.

I have realized my need to say goodbye and put to rest much of my childhood Bangladesh experiences to fully engage in life and ministry here and now. My hyperfixations on comparing my family’s life here in the past to my life here now has at times taken away my ability to fully engage with the reality in front of me.

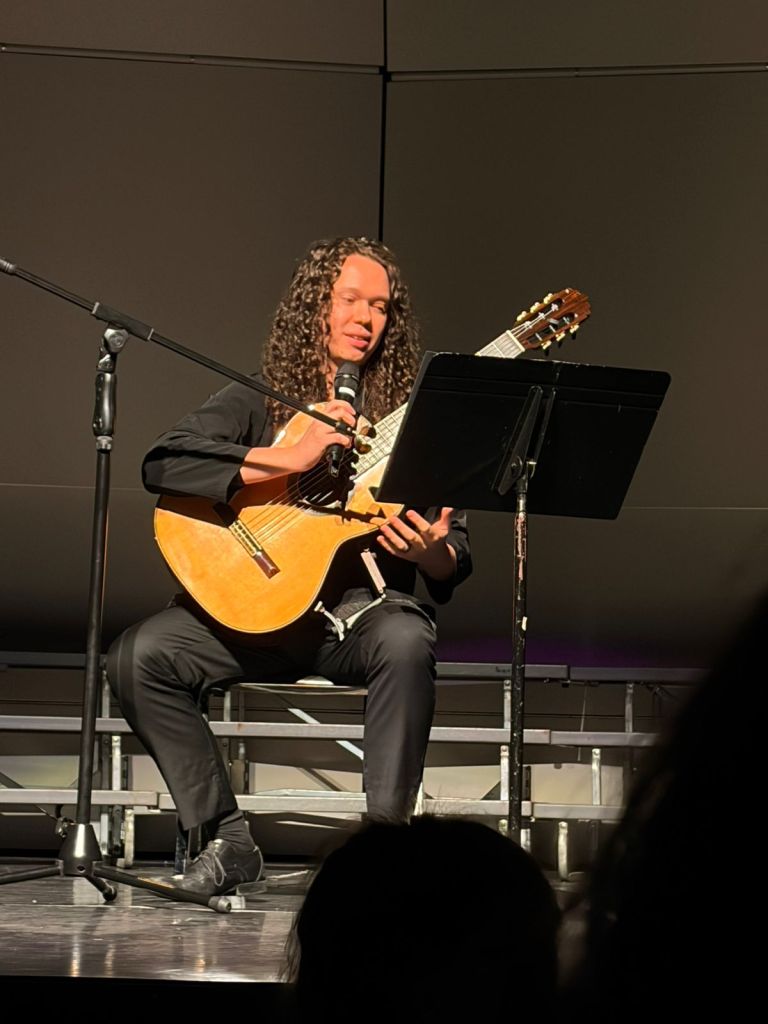

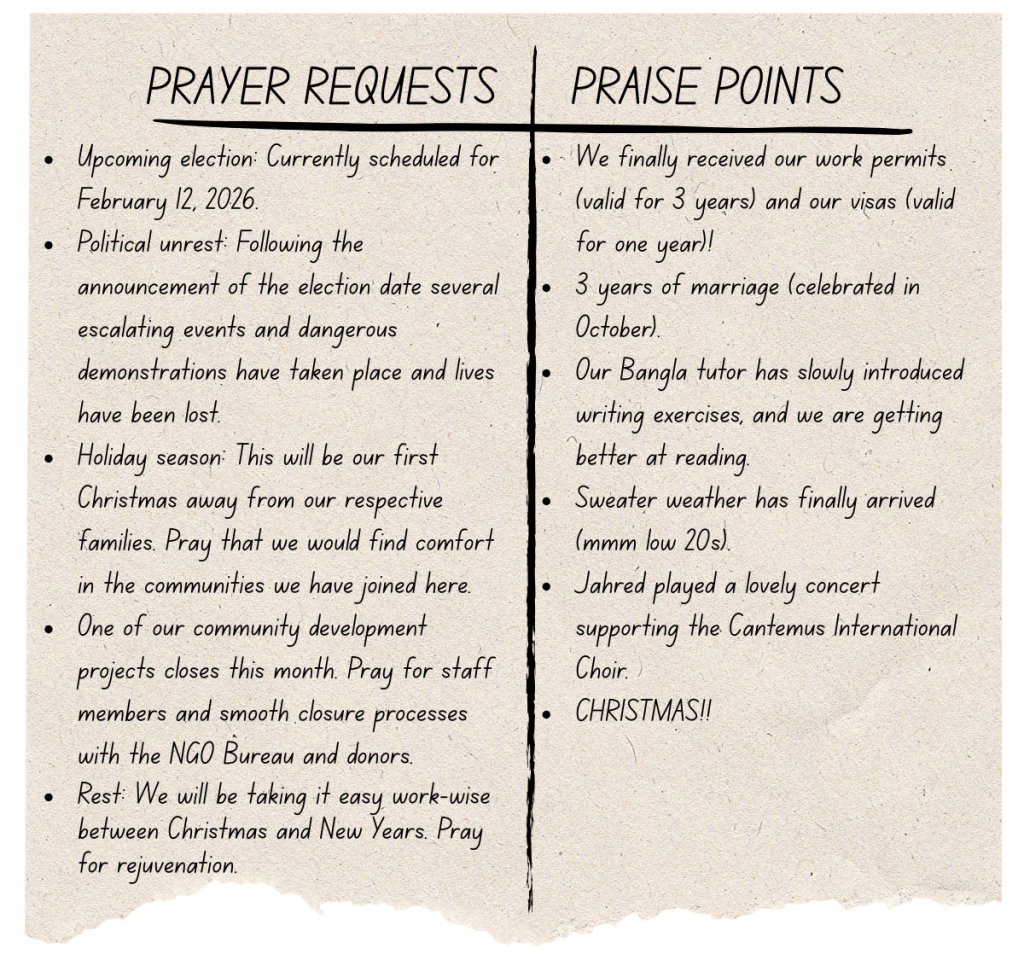

But still, connections from my past have brought me so many good things these past 7 months. Last month I played a concert with my Mom’s old choir, Cantamus. The 4 Schumann pieces I played from Kinderszenen Op. 15 (Scenes from Childhood) inspired and are the subheadings of this letter. Not to mention we would not have this opportunity or experience if it was not for the connections my family made in the golden years.

And so as we move forward, now with our work permits and visas obtained (WOOHOO – thank you for your prayers!) and more language under our belts, I am excited to continue engaging deeper in our relationships and work without fixating on my past or holding on to expectations for our lifestyles in the future.

The Poet Speaks

I have been asking myself why I am so focused on “doing life better than before” and trying to craft our lifestyle to this skewed vision. I think this in part comes from a desire to have something to measure success against and some method in which to trust. As if to say if we live a certain way, we can have assurance that our experience will be positive, productive, or pleasurable.

In this reflection I find myself coming back to Psalm 90, where the psalmist (believed to be Moses) makes the Lord God their dwelling place. Through all generations whether it be ancient times, 2005, or 2025, the Lord has and will direct and produce fruitful ministry when we simply dwell in Him. My parents, with their two young kids, no doubt abided in the way God called them to live. And that may or may not look different to the life Jessica and I have here. But the constant reminder I find myself needing is that I need not look to these external indicators of ‘successful’ ministry, but instead focus first on the ways God is working in me. How is He calling me to live and move through the world? He is the one who has and will set all things in motion and will continue to work through His people when we trust in Him.

As we continue to move through the seasons of life in Bangladesh I cry out,

“May the favour of the Lord our God rest upon us;

Establish the work of our hands for us –

Yes, establish the work of our hands.”

Psalm 90:17

Leave a comment